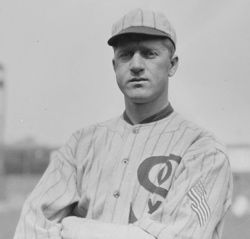

Red Faber

Baseball Hall of Famer and Cascade Native - Red Faber

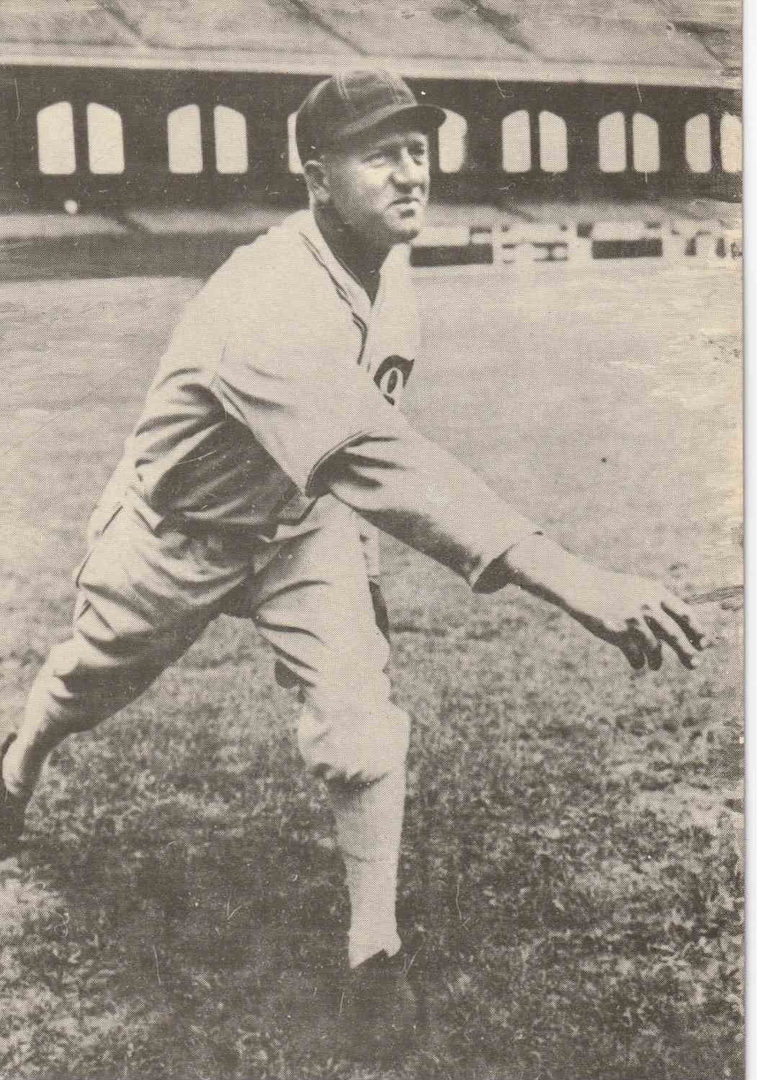

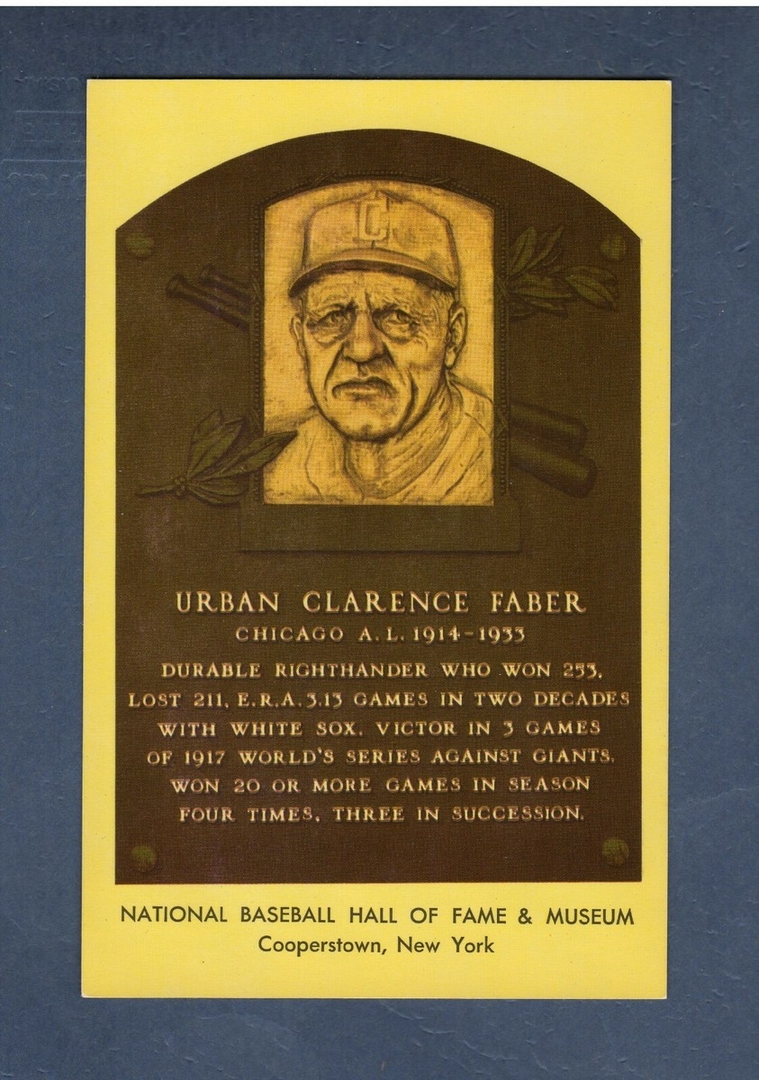

Cascade native Urban “Red” Faber (1888-1976), the second-to-last pitcher to legally throw a spitball in the major leagues, persevered through illness and injury, a world war and the Black Sox scandal to win a place in the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

The right-hander played his entire 20-year major league career (1914-33) with the White Sox, one of the league’s strongest teams before the Black Sox scandal and a perennial also-ran afterward. Faber won 254 games – a total that Ray Schalk, Faber’s long-time battery mate and friend, contended might have reached 300 had the team not been decimated by scandal.

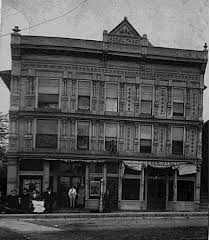

The Hotel Faber was constructed in 1893 by Red’s parents, Nicholas and Margaret. The building had on its main floor an office, lobby, dining room, “sample room” (where salesmen displayed and sold their wares) and a corner shop rented to small businesses. In 1944, after a half-century of ownership, the Faber family sold the hotel. The building still stands. (Photo courtesy of Judy Donovan, Cascade, Iowa.)

Childhood

Urban Clarence Faber (some references incorrectly list his middle name as Charles), was born on his parents’ farm near Cascade on September 6, 1888. The second of four children of Nicholas and Margaret Grief Faber, he was of Luxemburg descent. German was the primary language in the Faber home.

In 1893, the family moved into Cascade, where Nicholas operated a tavern and then opened the Hotel Faber. With his real estate holdings and successful hotel, Nicholas Faber became one of Cascade’s most affluent citizens.

In his early teens, Faber attended prep academies associated with colleges in two Mississippi River communities – Sacred Heart, in Prairie du Chien, Wisconsin, and then St. Joseph’s in Dubuque, Iowa.

It was during this period that he entertained thoughts of baseball as a career. He seriously considered baseball as a 16-year-old, when the Dubuque Tigers, a local club, paid him $2 for pitching Sunday games; the next season, he received $5.

Minor League

In 1909, when he was 20 and studying at a Dubuque business school, he joined the college varsity of his prep alma mater, St. Joseph’s. The team went undefeated in its half-dozen games. The highlight was Faber’s 22-strikeout performance against St. Ambrose College, which mustered only three hits.

Faber became known throughout the baseball community in Dubuque County, and one taking notice was Clarence “Pants” Rowland, former owner of Dubuque’s minor league team and an acquaintance of Chicago White Sox owner Charles Comiskey. (Rowland was between baseball jobs at the time, managing a hotel bar in Dubuque.)

Rowland encouraged Faber to sign with the Dubuque Miners, who were struggling in the Class B Three-I (Illinois-Indiana-Iowa) League. Joining the team with two months left in the 1909 season, Faber went 7-6. In August 1910, during his first full season as a professional, Faber (18-19) threw a perfect game against Davenport; only one ball reached the outfield. The Pittsburgh Pirates bought his contract the next day.

Faber made the Pirates’ 1911 Opening Day roster, but manager Fred Clarke never used him and in mid-May sent him to Minneapolis of the American Association. Within days of his arrival in Minnesota, Faber entered a distance-throwing contest and injured his pitching arm. During his short stay in Minneapolis, Faber had a career-changing experience: Teammate Harry Peaster taught him the finer points of the spitball, which at the time was a legal pitch.

Within weeks, the sore-armed Faber was shipped to Pueblo of the Western League. The young Iowan worked on his spitter over the next 2½ seasons, in Pueblo and then two years in Des Moines of the Western League. In the closing weeks of the 1913 season, White Sox owner Comiskey bought Faber’s contract for 1914.

The Majors

Faber’s off-season was abbreviated. In October 1913, Comiskey, at the urging of Rowland, belatedly added Faber to the White Sox roster for the around-the-world exhibition tour with the New York Giants. The rookie-to-be performed adequately on the domestic leg of the tour, but Comiskey planned to drop Faber from the squad before departure for Japan, Australia, the Mideast and Western Europe. However, Faber caught another break: Just hours before the teams embarked on their Pacific crossing, Giants pitcher Christy Mathewson, the most popular American athlete of the day, withdrew from the tour because he feared becoming seasick. Comiskey and Giants Manager John McGraw made an agreement: Faber was loaned to the Giants to take Mathewson’s place.

Mathewson must have felt vindicated in his decision. A powerful storm nearly wrecked the tourists’ ship as it crossed the Pacific, and all the passengers experienced bouts of seasickness. None suffered more than Faber, who was too ill to leave the ship for a day or two after its arrival in Japan. Eventually, Faber took regular turns pitching against his future team. In the finale in London, with King George V in attendance, Faber pitched tenaciously for 11 innings but took the loss.

Faber then joined the 1914 White Sox for his rookie season.

v

v

The White Sox

After a no-decision start and a handful of relief assignments, the 6-foot-2, 180-pounder forged into the national spotlight. On June 1, he pitched all 13 innings in a 2-1 loss to Detroit. Six days later, he earned his first career victory with a three-hit shutout of the Yankees. Ten days after that, he came within three outs of no-hitting defending World Series champion Philadelphia; an infielder’s slow work on a bouncer allowed the only hit. He cooled off in the second half of the season – a sore elbow sidelined him for a month – and finished 10-9 with a 2.68 ERA.

Before the 1915 season, Comiskey installed Rowland as White Sox manager, and Faber responded by elevating his game to new heights, posting a 24-14 record with a 2.55 ERA. Though the spitball was part of his repertoire, Faber also relied on his fastball and curve. He said that just the knowledge that he might unleash a spitter at any time was enough to keep most batters guessing.

His forte was getting hitters to swing early in the count and beat the ball into the ground. That skill was best demonstrated on May 12, 1915, in Comiskey Park, where he required a record-low 67 pitches to defeat Washington. Faber pitched less in 1916 due to injury, but he improved to 17-9 with a 2.02 ERA for a team that lost the pennant by two games.

Faber earned a reputation as a battler, and he held his own against the game’s greatest hitters.

In 1917, Faber posted a career-best 1.92 ERA, winning 16 games for the White Sox en route to their first pennant in eleven seasons. In the 1917 World Series against New York, Faber tied a series record with three victories. He won Game 2, lost Game 4, won Game 5 in relief and then closed out the host Giants with a complete-game victory in Game 6. His pitching performance overshadowed his baserunning blunder in Game 2, when he tried to steal third while it was occupied by teammate Buck Weaver.

After World War I

With World War I raging as the 1918 season opened, it appeared likely that major leaguers would be drafted into military service. As a 29-year-old bachelor, Faber was virtually certain to be conscripted. He won his first four decisions, enlisted in the Navy and lost his farewell game. Faber served his entire tour at Great Lakes Naval Base, near Chicago. A chief yeoman, he supervised recreation programs and pitched for the base team for the duration of the war.

Back in a baseball uniform for 1919, Faber (11-9) struggled with influenza – he was weak and underweight – and with arm and ankle injuries. After a layoff of several weeks, he struggled in his only appearance during the final month of the regular season and remained on the bench throughout the tainted 1919 World Series. Ray Schalk long contended that the Black Sox scandal would have been impossible had Faber been healthy; the conspirators would not have had enough pitching to succeed.

After the 1920 season, the 32-year-old Iowan married 22-year-old Milwaukee native Irene Margaret Walsh, of Chicago. The couple had no children, and she experienced ongoing health problems that reportedly included dependency on painkillers. Irene died in March 1943 of a cerebral hemorrhage at age 44

The advent of the “lively ball” era coincided with Faber’s best three-season performance (1920-22), when he went a combined 69-45 and lead the league in ERA for 1921 and 1922. He was among the 17 “grandfathered” pitchers still permitted to throw the otherwise banned spitball for the duration of his career.

In 1921, when the White Sox were a shambles after the Black Sox indictments, Faber’s 25 wins (against 15 losses) represented 40 percent of all the team’s victories. He followed that with his third consecutive 20-win season (21-17), despite playing for a team that finished 30 games under .500. After 1923, when he went 14-11, it was clear that Faber’s days of dominance were behind him; age, injury and White Sox ineptitude took their toll.

He suffered his first losing season (9-11) in 1924, when he got a late start after elbow surgery. As early as the mid-1920s, sportswriters started predicting Faber’s retirement. But he remained generally effective, and Red kept returning, season after season. He explained his longevity by noting that the spitball exerted less stress on his arm.

The Golden Years

Faber showed occasional flashes of his old form. He registered his third and final career one-hitter in 1929.

In 1932, new manager Lew Fonseca took him out of the starting rotation, and Faber’s record tumbled to 2-11, with all his losses coming in relief. By 1933, his 20th season in the majors, Faber (3-4) was the American League’s oldest player – he turned 45 that fall -- and its last “legal” spitballer. (A “grandfathered” National League spitballer, Burleigh Grimes, pitched 18 innings for the 1934 Yankees.) After a 5-15 record the previous two seasons, Faber was upset with his 1934 contract offer from the White Sox, who wanted to cut his pay by one-third, to $5,000. He secured his release and hoped to join another major league team, but there were no takers. He closed his career with a 254-213 record.

In retirement, Faber tried his hand at selling cars and real estate before acquiring a bowling alley in suburban Chicago. Early in the 1946 season, Ted Lyons became White Sox manager and hired Faber as pitching coach; they lasted three seasons. In April 1947, the 58-year-old Faber married 29-year-old divorcee Frances Knudtzon. They became parents the next year with the arrival of their only child, Urban C. Faber II.

In the mid-1950s, the Cook County (Ill.) Highway Department hired Faber; he worked on a survey crew until he was nearly 80. Exactly 50 years after his rookie season, in 1964, he was inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame. A lifelong smoker – he took up the habit at age 8 – Faber suffered heart and respiratory problems in his final years.

He died at home on September 25, 1976, at age 88. His grave marker in Chicago’s Acacia Park Cemetery cites his Navy service but makes no mention of his baseball glory.

Launch the media gallery 1 player

Launch the media gallery 1 player